Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

You may have a different relationship style than your partner. Couples can be together for many years & still not know what each other needs and wants.

You may have a different relationship style than your partner. Couples can be together for many years & still not know what each other needs and wants.

Because everyone responds differently in a relationship, it’s important to understand how our emotional brains are wired. Knowing this can stop us unwittingly “triggering” each other. Triggering can happen in less than one quarter of a second – much faster than we can consciously control. The balance of power between the emotional (limbic system) and thinking parts of our brain (orbitofrontal cortex) differs from person to person.

So you and your partner will be different in how quickly you become reactive, in how various parts of your brain interact with each other and in how you affect each other’s brains and bodies. It helps to know what’s your own relationship style and what’s your partner’s relationship style.

We are oriented to different styles of relating

Each of us comes to relationships oriented towards a certain style of relating. We may be aware of our partner’s style, but often not on a conscious level. When we’re not happy in the relationship, we usually insist on ignorance, saying things like “If I’d known you were like this, I’d never have gotten together with you!” There are reasons why we are so mystified & there are things we can do to overcome these challenges in relationships.

As a couples therapist, I’ve noticed these claims of ignorance about our partners are basically untrue, even though they may feel true when we say them. They’re untrue because our basic style of relating, our “social wiring” is set at a very early age due to the way we adapted to our parent’s (or carer’s) style of relating. This wiring is generally quite stable over time and remains almost unchanged as we mature, despite how intelligent we are, unless we consciously and repeatedly experience different ways of being with and relating to these processes.

The first stage of relationship can be deceiving

On first meeting our partner (in the honeymoon stage), we’re literally “auditioning” to enhance our chances of being chosen. We put our best self forward and are on our best behaviour at this stage. This is normal and appropriate, but is mostly done without the knowledge of how we or the other are wired to relate in a more committed relationship. During this first phase of relationship, we may give each other clues about our basic tendencies towards physical closeness, emotional intimacy and issues with security and safety. But it’s only when the relationship becomes more permanent in one or the other’s mind that these tendencies become manifest.

Most of what we do, we do without awareness, automatically, due to the way our emotional brains have been wired. Our brain’s reaction to physical closeness, distance and duration of closeness is wired from early childhood. It impacts how we sit and stand in relation to our partner, how we adjust the space between us, how we hug, make love and how we do everything involving physical movement and staying still.

Because we do this automatically, we’re usually totally unconscious of this aspect of our interactions. In addition, we handle physical closeness differently during the honeymoon/romantic stage than in the more committed stages of relationship. It’s common for couples to touch a lot when they’re dating, but this often reduces dramatically after making a commitment of some sort. This results in us wondering “Do I know you at all?”

We need an “owner’s manual” for our partner

Partners can be helped immensely by having an “owner’s manual” for each other and their relationship, one which assists in describing and understanding your own and your partner’s tendencies and relationship style. Recognizing each other’s styles makes it much easier to work as a team and more quickly resolve issues as they arise.

The styles presented here are found in Stan Tatkin’s book “Wired for Love”. He drew them from the research on attachment done by John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth and Mary Main. Tatkin found that most partners fall into one of three styles, but if you can’t decide which one fits you or your partner, don’t force it because we can be a blend of styles. Use these as a guide to understand and respect the human traits we all have, not as a way to judge yourself or your partner. These are normal and necessary adaptations we all make in childhood and in reaction to those we become close to in adulthood.

Relationship Styles of Attachment

In childhood, a secure relationship between carer and child is described as playful, interactive, flexible and sensitive. Bad feelings are quickly and appropriately soothed and good feelings like fun, excitement and novelty are prevalent, alongside comfort, relief and shelter. If this secure foundation was experienced often enough (no-one had these all the time) when we were children, we carry this through into adulthood. Tatkin calls these secure people an anchor.

It is a fact that not all of us had secure experiences in early childhoods. This could be because we had caregivers who weren’t always available, dependent or consistent. Or maybe one or the other of our caregivers valued other things more than relationship with us, like independence, money, performance, intelligence, beauty, obedience, privacy or loyalty. It’s not necessarily by choice, but due to life circumstances. A caregiver may have been physically or mentally unwell, had their own unresolved losses or trauma or they may have been immature.

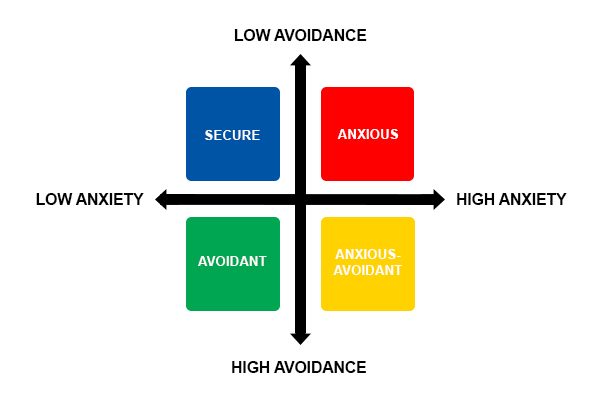

These and many other factors can interfere with a child’s sense of security. If this happened to us, as adults we approach relationships with an underlying insecure sense. There are two main styles of insecure attachment. One can lead us to avoid too much contact and tend to want to keep to ourselves, due to a sense of being an island in the ocean of humanity. The other insecure attachment style can lead us to feel ambivalent about getting close to others, rendering us more like a wave in the ocean.

By understanding how you and your partner are biologically wired, treating this with respect and building trust between the two of you, waves and islands can also influence each other to become more anchor-like by creating a secure relationship (called earned secure attachment) where each knows where the other stands.

Anchors – Secure relationship attachment style

“Two can be better than one”.

Anchors are not overly needy or clingy, they don’t feel anxious about getting too close or moving too far away from their partner. They generally make upbeat contact by phone or email if apart and are usually unafraid to share fully what’s on their mind without being too preoccupied that there will be negative consequences for doing so. They respect each other’s feelings and connect with each other first to share good and bad news. They are attuned to each other in private and public, noticing cues of distress and act quickly to provide relief. Each makes the effort to learn how the other works and creates an internal “owner’s manual” that they frequently use and add to as the relationship matures.

They work at ensuring their relationship is secure enough so that both can continue to grow together and individually. Because of this, they use the relationship as an anchoring device during times when the world feels chaotic. They’re generally happy people, usually grateful for the people and things in their world. They take good care of themselves and their relationships, and have an expectation that committed partnerships are satisfying, supportive and respectful.

Anchors usually don’t bother with unsafe or non reciprocal relationships. In relationships, when the going gets tough, or when they get frustrated, they don’t give up but draw on their memories of previous challenges they’ve successfully overcome together. They are unafraid to admit errors and are quick to repair injuries or misunderstandings knowing that the first to do so “wins” in getting the relationship back on track. They are good at coping with relationship challenges that tend to overwhelm non-anchors.

Answer these questions:

• I’m fine by myself, but I prefer the give-and-take of an intimate relationship.

• I value my close relationships and will do what it takes to keep them in good condition.

• I get along with a wide variety of people.

• I love people, and people tend to love me.

• My close relationships aren’t fragile.

• Lots of physical affection and contact is fine with me.

• I’m equally relaxed when I’m with my partner and when I’m alone.

• Interruptions by my loved ones do not bother me.

During conflict, anchors tend to have the most balanced interactions between their emotional and thinking brains. They can more quickly bring themselves and their relationships back into harmony. During times of distress, islands and waves have an ineffectual thinking brains, making them more likely to “go to war” with their partner. This can be rewired, via regular self-soothing practices plus interactions with more anchored others, so that reactivity and arousal becomes easier to manage.

Islands – Avoidant relationship attachment style

“I want you in the house, just not in my room … unless I ask you.”

An island’s actions and reactions have a basis in their physical makeup. These patterns have been there from a very early age. An island feels it’s okay to be angry when their partner intrudes upon their space because they often spent a lot of their childhood alone. Their carers rarely wanted or gave them physical contact, so they learnt early that it was better not to turn to others for support or affection. They focus on taking care of themselves and don’t expect frequent interactions with partners, including sexual intimacy.

They enjoy their partner’s company, but find it hard to shift out of alone time and often feel as if their partner is trying to get them to do something against their will. They tend to resist coming closer, but with enough coaxing for them to come out can enjoy being with their partner. Yet when left alone, even briefly, they’ll go back into their own internal world.

Islands believe their alone time is a choice and are not aware that it comes from their normal childhood needs to connect having being ignored or dismissed. They often confuse autonomy and independence with how they adapted to not being responded to. If one or both partners are addicted to alone time, relationship problems can arise because islands avoid being too close.

Their feelings of loneliness are hidden by the absorbed state they create when alone. Islands tend to experience more stress when around people than do anchors or waves, due to a higher sense of threat when in proximity to significant others or in social situations. Two islands in relationship can spell trouble because of their high tolerance for being away from each other. Tatkin says that if tolerating time alone were comparable to holding one’s breath underwater, islands could hold their breath much longer than anybody else.

Islands tend to look toward the future, avoiding looking at present relationship conflicts or learning from past relationship issues, including childhood ones. Without the help of their partner, islands generally do not understand who they are, don’t recognise their deep existential loneliness, nor do they overcome their anxiety about intimate relationships. Receiving understanding from another is the medicine which allows them to leave their island and enter a more social world. They crave partners who will make the effort to find out what makes them tick.

Answer these questions:

• I know how to take care of myself better than anybody else could.

• I’m a do-it-yourself kind of person.

• I thrive when I can spend time alone in my own private sanctuary.

• If you upset me, I have to be by myself to calm down.

• I often feel my partner wants or needs something from me that I can’t give.

• I’m most relaxed when no-one else is around.

• I’m low maintenance, and I prefer a partner who is also low maintenance.

During conflict, islands rely too much on talking to work out issues because they can’t easily connect on non-verbal levels. In an argument, they can appear overly logical, rational, arrogant, unemotional, unexpressive or insufficiently empathic. Under stress, islands can become dismissive, inflexible, or too silent and still. They will focus on the future and avoid the present and the past, saying things like “The past is over. Can’t we just move forward?”

In extreme stress, their thinking gets hijacked and they communicate attack or retreat, using or withholding words as weapons. Ideally their partner could get through by using verbal friendliness. If you are centered enough, try talking your partner down, being reassuring, calming and rational. Say things like “What you’re saying makes sense”, “You’re right about that” or “You’ve made a good point.” A wild island has little sense of what they are feeling, and is poor at communicating feelings or picking up feelings from their partner. The partner of an island may also have trouble doing these things, because emotions are contagious and emotional brains set each other vibrating.

Waves – Anxious relationship attachment style

“If only you loved me like I love you”, “I can’t do it with or without you”.

The insecurity in a wave comes from interactions with their earliest caregivers and is usually repeated in later relationships unless they have experiences which help rewire their brains. They usually remember their childhoods well and still hold anger at their parents. They remember when carers have been insensitive or selfish.

Even though they may have been kissed and held, waves focus on the times their carers were frustrated with them, unavailable, or too preoccupied with their own needs to meet the wave’s needs. Waves valued spending time with their carers, they talked a lot, but often felt or were told they were too needy. As children, they were often left with babysitters or ignored.

Waves don’t provide any sense of security or stability, they cause perpetual disturbances, going up and down, rushing in and rushing out. They’re preoccupied with fear, anger and ambivalence about being close. They can’t move forward because they’re caught in past injustices and hurts which flow in and out like waves. If both partners are waves, there is a lot of turmoil, like a push-pull alternation between being close and being standoffish. There’s usually a fair bit of drama because waves respond by making more waves.

They’re ambivalent because they want to connect but are afraid of connecting. They alternate between feeling wanted and rejected, believing eventually their partner will reject them so they hold back from feeling good, relieved, comforted. They believe it’s better to reject before being rejected, to leave before being left. They come close to a partner hoping for connection, then pull back fearing disappointment.

When leaving or reuniting with a partner, they often get angry and cause a fight which confuses them as much as it does their partner. They’re aware of their need to depend, but believe it’ll be too much for others, so they anticipate being dropped or abandoned. This can be such a strong anticipation that they create rejection from their partner because of their fear and negativity.

Waves often refuse to look forward, remaining stuck on past or current conflicts believing that unless these are resolved, they’re not sufficiently reassured that it won’t happen again. Their insecurity can appear bottomless, as does their need for frequent contact and reassurance. To shift this pattern, a wave’s partner needs to experiment with moving physically and emotionally forward, so as to help overcome childhood injuries and shift them from feeling threatened to feeling loved. Waves must also do the counter-intuitive and apologise as soon as they realise they’ve been negative or hostile.

Answer these questions:

• I take better care of others than I do of myself.

• I often feel as though I’m giving and giving and not getting anything back.

• I thrive on talking to and interacting with others.

• If you upset me, I have to talk in order to calm down.

• My partner tends to be rather selfish and self-centered.

• I’m most relaxed when I’m around my friends.

• Love relationships are ultimately disappointing and exhausting. You can never really depend on anyone.

During conflict, waves may insist too much on being verbally reassured that they’re loved and secure. They’re overly focused on getting these assurances and may look and sound dramatic, emotional, overly expressive, off the point, irrational and angry. They can come across like a hailstorm. Under stress, a wave can be punishing, rejecting, unforgiving and inflexible. During conflict, a wave tends to focus on the past and avoids the present or future, saying things like “I can’t move forward until we resolve what happened.”

In high stress, when their brain gets hijacked, they can become threatening by insisting on finding a resolution right now. They try to connect by using physical and emotional means as weapons. You can attempt reaching out non-verbally to your wave partner. If your own right brain hasn’t been hijacked, try disarming your partner through non-verbal friendliness, touch them gently, provide a calm presence. Be reassuring and soothing, especially when speaking.

For help in managing your own & your partner’s relationship styles, Call 0421 961 687 or email us to schedule an appointment. International callers should call +61 421 961 687.

You deserve the best trained relationship coaches if you’re planning to invest time and money in your relationship. If you’re not ready to book an appointment, call us on 0421 961 687 to book a FREE 15 minute phone consultation to discuss how we may be able to assist you.

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

I have this book marked and find it VERY helpful trying to deal with my extreme island bf (I’m a wave). Have any suggestions for how to communicate without putting on the defensive, I have a knack for this! I want to let him know when my needs are not being met, how to ask for his time without it seeming like a demand or expectative, and how to show him he can get his alone time with me still in his presence. Thanks in advance!

Hi Mel, good on you for having found a method to bring things up with your bf. You might find this page useful as it has many tips.

Thanks for a very clear summary, Vivian. You have explained Stan’s ideas in a very non- threatening and non-stigmatising way that many can relate to- I will definitely share,

Hi Gloria, thanks for that. I find his terms for the attachment categories very useful for couples work. Glad that you want to pass this on to your couples.

Hi Vivían,

a ‘wild island’ ey? I have been a wild island plenty of times in my relationship, oh do I know how that feels…

How well I can relate to all those poor hijacked thinking brains and wild islands floating around in the ocean of humanity. That is such a lovely and captivating image. It makes so much sense.

Thank you so much for sharing that! I am definitely going to read Stan Tatkin’s book. It sounds great!

Steph

Hi Stephanie, I think you’ll get a lot out of reading it. He explains some of our relationship dynamics which result from early attachments very clearly & in ways which are easy to understand & then put into action. Of course (just to complicate things) there are also other ways to understand relationship patterns. Vivian.