Psychotherapy Redeemed

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

“Psychotherapy Redeemed” is my response to the much admired Dr. Harriet Hall, aiming to balance some unwarranted claims about psychotherapy.

Harriet Hall, was a medical doctor, science communicator and skeptic. On reading her article in Skeptic magazine called “Psychotherapy Reconsidered”, I felt impelled to offer some contrasting considerations, backed by data, to balance her claims that no-one can provide an objective report about the psychotherapy field. She stated that there “…aren’t even any basic numbers,” that we don’t know whether psychotherapy works, that it is not based on solid science, and that there is “…no rational basis for choosing a therapy or therapist.”

My response was published in December 2023 in Skeptic Magazine, 28(4), pp.53–57. It’s posted below with the permission of the Skeptics Society.

Article

While not going so far as arguing, as some have, that psychotherapy is always effective, I’d like to present some data and offer some contrasting considerations to Harriet Hall’s recent SKEPTIC article. Probably no other area within social science practice has been so inordinately and unfortunately praised and damned. Many of us working in the field have long been acutely aware of the difficulties to which Hall and others point, as well as other problems. However, we also regularly observe the positive changes in clients’ lives that psychotherapy—properly practiced—has produced, and in many cases, the lives it has saved.

In her article, the late Harriet Hall, whose work I and all skeptics admire and now miss, stated that no-one can provide an objective report about the field, indeed, that there “…aren’t even any basic numbers,” that we don’t know whether psychotherapy works, that it is not based on solid science, and that there is “…no rational basis for choosing a therapy or therapist.”

Hall and other sources she quotes are quite correct in saying that there is much we still don’t know about human psychology, and much that we don’t understand about how the mind and psychotherapy work.

Yet it’s also necessary to look at the data and analyses that demonstrate that psychotherapy does work. The case for the defense is made in detail in The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work by Bruce Wampold and Zac Imel, and also in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work by Wampold and John Norcross, both of which present decades of meta-analyses. They review conclusions from an impressive number of psychotherapy studies and show how humans heal in a social context, as well as offer a compelling alternative to the conventional approach to psychotherapy research, which typically concentrates on identifying the most effective treatment for specific disorders by placing an emphasis on the particular components of treatment.

This is a misguided point in Hall’s argument, as she was looking at the differences between treatments rather than between therapists. Studies that previously claimed superiority over one method to another ignored who the treatment provider was.1 We know that these wrong research questions arise from using the medical model where it is imperative to know which treatment is the most effective for a particular disorder. In psychotherapy, and to some extent in medicine generally, the person administering the treatment is absolutely critical. Indeed, in psychotherapy the most important factor is the skill, confidence, and interpersonal flexibility of the therapist delivering the treatment, not the model, method, or “school” they use, their number of years in practice, or even the amount of professional development they’ve had. How we train and supervise therapists largely has little impact on the outcomes of psychotherapy, unless each therapist routinely collects outcome data in every session and adjusts their approach to accommodate each client’s feedback.

The Bad News About Psychotherapy

Hall is right on the point that psychotherapy outcomes have not improved much over the last 50 years. Hans Eysenck’s classic study debunking psychotherapy was performed in 1952.2 His view was not challenged until 1977, when a meta-analysis showed that psychotherapy was effective, and that Eysenck was wrong.3 It found the effect size (ES) for psychotherapy was .8 above the mean of the untreated sample. Recent meta-analyses show that this ES has remained the same over the intervening 50 years, despite the proliferation of diagnoses and treatment models.4

Hall was also accurate in saying that much conflicting data exists from studies about the efficacy of the hundreds of types of psychotherapy. Yet she was incorrect in saying that we don’t even have basic numbers. We now have decades of meta-analyses showing what works and what doesn’t work in psychotherapy. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Hall was also mostly on-target when she stated, “…proponents of each modality of psychotherapy give us their…impressions about the success of their chosen method.” Decades of clinical trials comparing treatment A to treatment B point to the conclusion that all bona fide psychotherapy models work equally well. This is consistently replicated in trials comparing therapists who use two different yet coherent, convincing, and structured treatments, as long as these treatments provide an explanation for what’s bothering the client in addition to discussing a treatment plan for the client to work hard at overcoming their difficulties. Psychotherapy research clearly shows that all models contribute 0–1 percent towards the outcomes of psychotherapy.11 This means that proponents of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy—or any model—claiming its superiority to other treatments, are not basing their claims on the available evidence.

Another correct statement of Hall’s is that most therapists have no evidence to show that what they’re doing is effective. This lack of evidence led others to conclude that, “Beyond personal impressions and informal feedback, the majority of therapists have no hard, verifiable evidence that anything they do makes a difference…Absent a valid and reliable assessment of their performance, it also stands to reason they cannot possibly know what kind of instruction or guidance would help them improve.”12

For decades, free pen-and-paper measures by which therapists can track their outcomes have been available,13 recently superseded by online versions.14 These Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT) online platforms are easy to use and have been utilized by thousands of therapists around the world to get routine feedback from every client on each session. The result: Data from hundreds of thousands of clients is continually being updated. Regrettably, those of us who use these methods are still a small minority of therapists practicing around the world compared to the unknown numbers who, as Hall rightly pointed out, provide psychotherapy in its manifold (and perhaps unregulated) forms.

The online outcome measurement platforms mentioned above are recommended by the International Center for Clinical Excellence (ICCE).15 For decades, the ICCE has been aggregating data from therapists around the world and so providing evidence that corroborates some of Hall’s critical claims about psychotherapy. Current data show that dropout rates, defined as clients unilaterally stopping treatment without experiencing reliable clinical improvement, are between 20–22 percent among adult populations (even when therapists use FIT).16 Dropout rates are typically higher (40–60 percent) for child and adolescent populations. This raises the unfortunate possibility that dropout rates for therapists who don’t get routine feedback from clients are probably higher still.

Hall was, however, incorrect in stating that we don’t know about the harms of psychotherapy. There are many examples of discussions and analyses of what doesn’t work in psychotherapy and what can cause harm.17 One study of aggregated data shows that the percentage of people who are reliably worse while in treatment is 5–10 percent.18

Regrettably, the data indicate that the average clinician’s outcomes plateau relatively early in their career, despite their thinking they are improving.

One review found no evidence that therapists improve beyond their first 50 hours of training in terms of their effectiveness, and a number of studies have found that paraprofessionals with perhaps six weeks of training achieve outcomes on par with psychologists holding a PhD, which is equal to five years of training.19

These data support Hall’s statement that unless they are measuring their outcomes, no therapist knows whether their method is more (or less) effective than the methods used by others. Even then, it leads to a conflation that it’s due to the method instead of the therapist. Studies also show that students often achieve outcomes that are on par or better than their instructors. These facts are amply demonstrated in Witkowski’s discussion with Vikram H. Patel,20 whose mental health care manual Where There Is No Psychiatrist is used primarily in developing countries by non-specialist health workers and volunteers.21

Further, there is now evidence that psychotherapists who have been in practice for a few years see themselves as improving even though the data show no such improvement.22 Psychotherapists are not immune either to cognitive biases or to the Dunning-Kruger effect, and a majority rate themselves as being above average. In other words, psychotherapists generally overestimate their abilities. Finally, meta-analyses show that there is a large variation in effectiveness between clinicians, with a small minority of top performing therapists routinely getting superior outcomes with a wide range of clients. Unfortunately, these “supershrinks” are a rare breed.23

To balance the bad news above, following is some of the data which shows that psychotherapy works.

The Good News About Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy works. It does help people. Since Eysenck’s time and in response to the numerous sources cited by Hall, many studies have demonstrated that the average treated client is better off than eighty percent of the untreated sample.24 That doesn’t mean that psychotherapy is eighty percent effective, but it does mean that if you take the average treated person and you compare them to those in an untreated sample, that average treated person is doing better than eighty percent of people in the untreated sample. This effect size means that psychotherapy outcomes are equivalent to those for coronary artery bypass surgery and four times greater than those for the use of fluoride in preventing tooth decay. As discussed earlier, this has remained constant for 50 years, regardless of the problem being tested or the method being employed.

Just as in surgery, the tools that psychotherapists use are only as effective as the hands that use them. How effective are psychotherapists? Real world studies have looked at this question, asking clinicians to measure their outcomes on a routine basis with each client in every session. They’ve compared these outcomes against those in randomized clinical trials (RCTS).

It must be noted that in RCTs researchers have many advantages that real world practitioners do not. These include: (a) a highly select clientele, in that many published studies have a single unitary diagnosis while clinicians routinely deal with clients with two or more comorbidities; (b) they have a lower caseload; and (c) they have ongoing supervision and consultation with some of the world’s leading experts on psychotherapy. Despite all this, the data documents that psychotherapy outcomes are equivalent with those of RCTs.25

Therapists around the world, including me, have been using Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT) for decades. I have been seeing clients since 1981 and my clinical outcomes started to improve when I started incorporating FIT into my practice nearly 20 years ago. Those of us who use FIT routinely get quantitative feedback from every client at the beginning of every session. We ask about the client’s view of the outcomes of therapy in four areas of their life: (1) their individual wellbeing; (2) their close personal relationships; (3) their social interactions; and (4) their overall functioning. This measure is termed the Outcome Rating Scale or ORS.26 At the end of every session, we also get quantitative feedback about four items to gauge the client’s experience of: (1) whether they felt heard, understood, and respected by us in that session; (2) whether we talked about what the client wanted to discuss; (3) whether the therapist’s approach/method was a good fit for the client; and (4) an overall rating for the session, also asking if there was anything missing in that session. This measure is termed the Session Rating Scale or SRS.27 The resulting feedback is successively incorporated into the therapy, ensuring that the client’s voice and preferences are privileged.

Research shows that individual therapists vary widely in their ability to achieve positive outcomes in therapy, so which therapist a client sees is a big factor in determining the outcome of their therapy. Data gathered over a 2.5-year period from nearly 2,000 clients and 91 therapists documented significant variation in effectiveness among the clinicians in the study and found certain high-performing therapists were 10 times more effective than the average clinician.28 One variable that strongly accounted for this difference in outcome effectiveness was the amount of time these therapists devoted outside of therapy to deliberately practicing objectives which were just beyond their level of proficiency.29

What these studies show is that we’ve been looking in the wrong place for the answers as to why the outcomes of psychotherapy have not improved over the last 50 years. We’ve been studying the effects within the therapy room rather than what happens outside of the therapy room, i.e., what clients bring into their therapy and what therapists do before and after they see their clients.

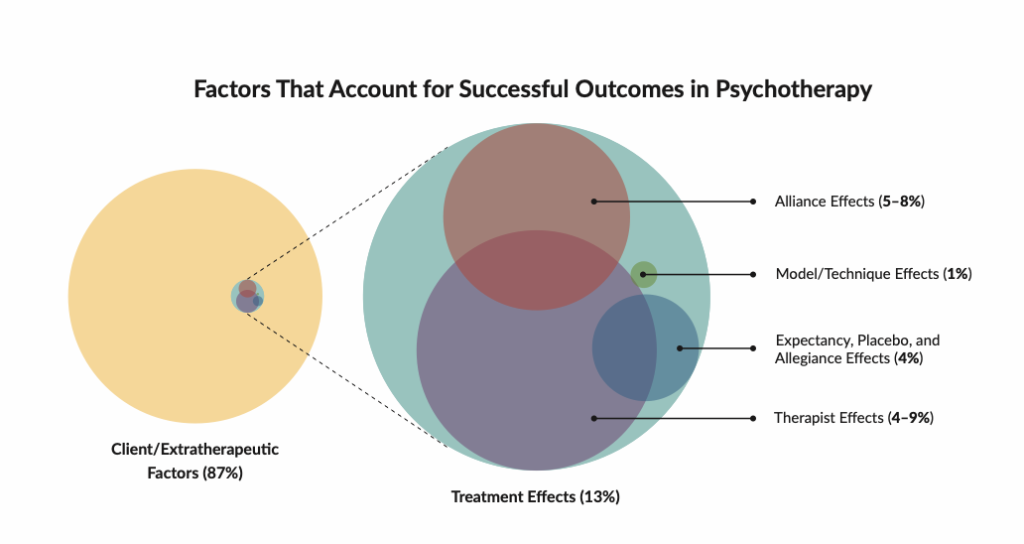

Indeed, clients and their extra-therapeutic factors contribute 87 percent to outcomes of psychotherapy!30 Extra-therapeutic factors comprise the client’s personality, their daily environment, their friends, family, work, good relationships, and community support. On average clients spend less than one hour per week with a therapist. The extra-therapeutic factors are the components of the client’s life to which they return, and which make up the other 167 hours of their week. This begs the question “does this mean that there’s nothing we can do about it?” The key is for therapists to a) attune to these outside factors and resources, and b) tap into them. The remaining 13 percent of treatment effects which accounts for positive outcomes in therapy is made up of: the individual therapist, between 4–9 percent; the working alliance (relationship) between therapist and client, 4.9–8 percent; the expectancy/placebo and rationale for treatment, 4 percent; while the model of therapy contributes an insignificant 0–1 percent. This highlights that who the therapist is and how they relate to their clients is the main variable accounting for positive outcomes outside of the client’s extra-therapeutic factors.

So, how should you choose a therapist?

There is now a movement led by eminent researchers, educators, policymakers, and supervisors in the psychotherapy field to ensure that after graduation therapists consciously and intentionally engage in ongoing Deliberate Practice—critically analyzing their own skills and therapy session performance, continuously practicing their skillset (particularly training their in-the-moment responses to emotionally challenging clients and situations), and seeking expert feedback. Deliberate Practice is based on K. Anders Ericsson’s (who made a name for himself as “the expert on expertise”) three decades of research on the components of expertise in many domains of activity, including in sport, medicine, music, mathematics, business, education, computer programming, and other fields. Building on research in other professional domains such as sports, music, and medicine, a 2015 study was conducted to understand what differentiated top performing therapists from average ones.31 It found that top performing therapists spent 2.5 times more time in Deliberate Practice before and after their client sessions than did average therapists, and 14 times more time in Deliberate Practice than the least effective therapists!

Experts in the field encourage therapists, supervisors, educators, and licensing bodies to “change the rules” about how psychotherapists are trained and how psychotherapy is practiced.32 The research reviewed here highlights that we can do this in two main ways: first, by making our clients’ voices the central focus of psychotherapy by routinely engaging in Feedback Informed Treatment with every client in every session to create a culture of feedback; and second, by each therapist receiving guidance from a coach who uses Deliberate Practice. To ensure accountability to clients, health insurance companies, and the psychotherapy field itself, this should be the basis for all practice, training, accreditation, and ongoing licensing of therapists.

In summary, psychotherapy does work. For readers who are curious to explore why psychotherapy works and which factors contribute to it doing so, I’d highly recommend Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness33 and its accompanying Field Guide to Better Results.34

Vivian Baruch is a relationship coach, counselor, psychotherapist, and clinical supervisor specializing in relationship issues for singles and couples. She has been practicing since 1981, has been a psychotherapy educator at the Australian College of Applied Psychology, and taught supervision to psychotherapists at the University of Canberra. In 2004, she trained with Scott D. Miller, and has been using Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT) for 20 years to routinely incorporate her clients’ feedback into her psychotherapy and supervision work.

REFERENCES

4 Miller, S.D., Hubble, M.A., & Chow, D. (2020). Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness. American Psychological Association.

5 Wampold, B.E., & Imel, Z.E. (2015). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work. Routledge.

6 Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (Eds.). (2019). Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Volume 2: Evidence-Based Therapist Responsiveness. Oxford University Press.

11 Wampold, B.E., & Imel, Z.E. (2015). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work. Routledge.

12 Miller, S.D., Hubble, M.A., & Chow, D. (2020). Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness. American Psychological Association.

20 Witkowski, T. (2020). Shaping Psychology: Perspectives on Legacy, Controversy and the Future of the Field. Springer Nature.

21 Patel, V. (2003). Where There Is No Psychiatrist: A Mental Health Care Manual. RCPsych publications.

22 Miller, S.D., Hubble, M.A., & Chow, D. (2020). Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness. American Psychological Association.

23 Ricks, D. F. (1974). Supershrink: Methods of a Therapist Judged Successful on the Basis of Adult Outcomes of Adolescent Patients. In D.F. Ricks, A. Thomas, & M. Roff (Eds.), Life History Research in Psychopathology: III. University of Minnesota Press.

27 Ibid.

30 Wampold, B.E., & Imel, Z.E. (2015). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work. Routledge.

33 Miller, S.D., Hubble, M.A., & Chow, D. (2020). Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness. American Psychological Association.

Published December 2023 – Baruch, V. (2023). Psychotherapy Redeemed. Skeptic magazine, 28(4), pp.53–57. https://www.skeptic.com/magazine/archives/vol28n04.html